Lessons from an “Unhinged Traveller” Who’s Not Afraid to Die

A post-Stranger Conversations chat with Singaporean globetrotter Toh Yi Rong on near-death experiences, detours, and daring to live on the edge.

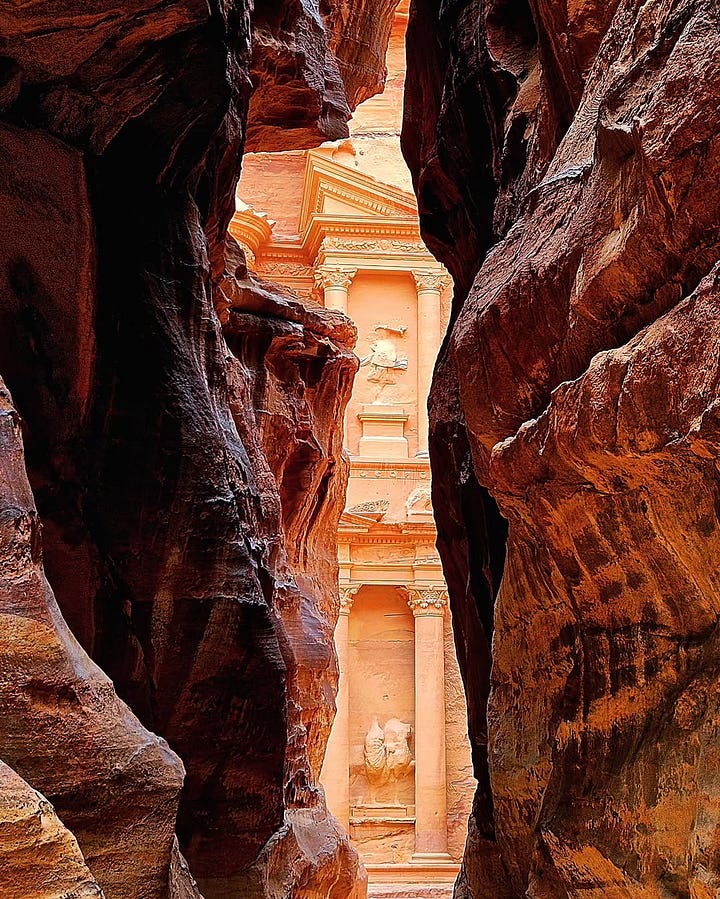

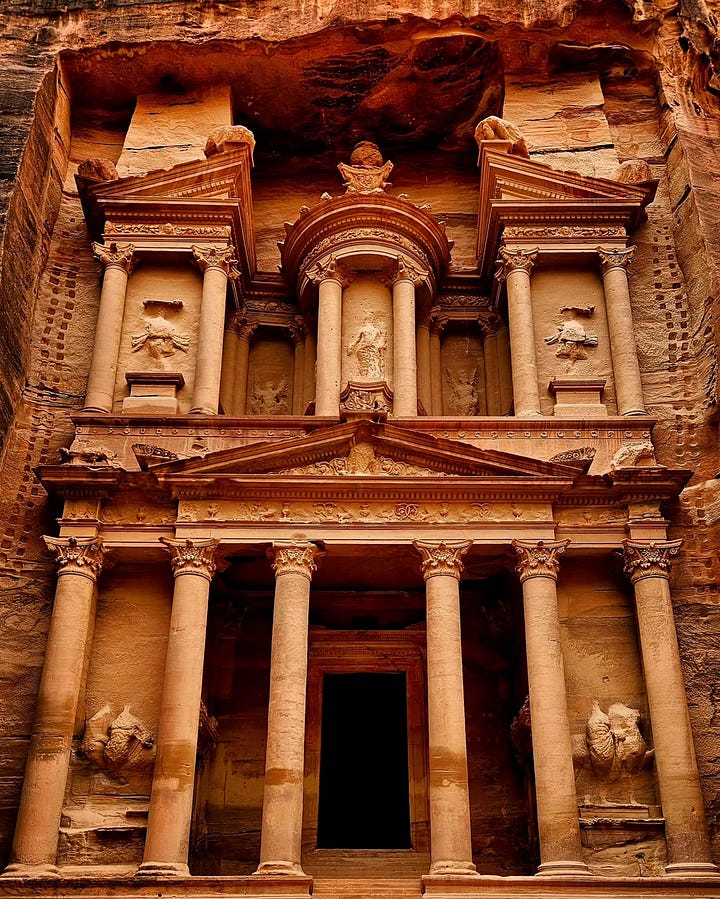

At 30, Toh Yi Rong has already travelled to 100 countries and autonomous regions—many of which most people would think twice about visiting. She’s ridden the infamous Iron Ore Train across the Sahara Desert in the dead of the night, navigated civil unrest in Ethiopia, explored the archaeological ruins of Sabratha and Leptis Magna, Libya, and conducted giant tortoise research in the Galápagos Islands. Her passport reads more like an international dossier than a holiday itinerary.

The modern-day “Indiana Jane” wasn’t always this way.

“I absolutely hated travelling growing up,” she laughs. Raised in Singapore, her childhood was filled with family vacations comprising rushed group tours, whirlwind itineraries, and the blur of hotel rooms. But she was also a voracious reader. Encyclopedias and textbooks became her portals to faraway lands—feeding a burgeoning desire to see wild animals, Nepal’s majestic mountains, and San Marino’s imposing citadels. One day, she vowed, she would step foot in these places on her own terms.

The Beginnings of a Rogue Explorer

That spark never left. While studying environmental sciences in the UK, Yi Rong took matters into her own hands. Tired of waiting for friends to commit to weekend trips, she packed her bags. “I’m going,” she said. “And for more than just a weekend. I’ll make this my life.”

Over three years, Yi Rong backpacked across 40 countries (mainly in Europe) on a student budget—often slumming it, making rookie mistakes, and stumbling through mishaps. But what she gained was far more valuable: a lifelong hunger for discovery. “The more I travelled, the more alive I felt. I started thinking, how far can I go? What more can I do?” Like Moana from Disney, she jokes, she was answering a call.

After graduating, Yi Rong returned to Singapore where she juggled an unconventional mix of roles: agricultural biotech, brewing beer from surplus bread, and running R&D at an alternative coffee startup. Still, the itch to escape never left. With each break, her trips grew more daring and ambitious.

“I’m Not Scared to Die”

By then, she had already visited 72 countries and spent most of her salary on travel. Her inquisitive nature kept pulling her toward far-flung corners of the world.

“People always ask me, ‘Why do you want to go to these places? Why do you want to do that?” Yi Rong says. “The reason is simple: I’m just naturally curious. I want to see anything and everything.” She speaks with refreshing candour, coming across as articulate, sharp-tongued, and deadpan in her humour.

Some might balk at the places she’s chosen to visit—regions often deemed conventionally dangerous. But Yi Rong’s drive comes from something deeper than wanderlust.

“The truth is, I’m not scared to die,” she says. Having grown up in a home shattered by domestic violence, she knows that sometimes the most dangerous place is one’s own backyard. Her father is no longer in her life. “When the one place that is supposed to be a safe haven is not safe—really, how much worse could the outside world be?”

In 2023, she found herself stuck in a job that sapped all her energy and joie de vivre. She was burnt out, constantly on antibiotics for respiratory problems, and was juggling being a first-time caregiver to a family member with dementia. She began pooling her resources, planning to eventually quit her job and travel full-time for a year. “I brought this up at a networking session filled with people I really admire and couldn’t believe the response I got,” she says. “Everyone was so excited for me. For the first time in months, I felt validated and celebrated. I knew I had made the right decision.”

It hardly came as a surprise when, two weeks later, her bosses sat her down, told her she had no aptitude at her job, and asked her to leave. Rather than being disappointed, she jumped at the opportunity to commence her travels earlier than expected. In May 2024, Yi Rong left for Canada, and hasn’t stopped moving since. She’s slept in cabins, tents, and everywhere in between. Along the way, she’s racked up the kind of wild, epic adventures most people only dream of in a lifetime.

What Visiting 100 Countries Taught Yi Rong

I first met Yi Rong at a Stranger Conversations event titled ‘The Raw Truths About Travel’ earlier this year, and left deeply inspired by her life experiences. She shares her lessons with the irreverence and honesty of someone who’s been through it all.

1. Travel with Curiosity, Not Judgment

I’ve been to countries people stereotype as dangerous—Iraq, Libya, Eritrea, to name a few. But honestly, stereotypes form because of what we read about in the mainstream media.

There’s no substitute for being somewhere physically and learning for yourself. In parts of Africa and the Middle East, I met people who had been through war, and they were some of the warmest, friendliest people I’ve ever known. In Libya, for example, people were waving to us on the street. They welcomed us with open arms and said, “Welcome to Libya. We are free.” I still think about that.

2. Money Matters and Privilege

It’s not always easy. When I was still working a regular job, most of my salary went towards travelling. Now, I fund my travels mostly through savings, investments, and part-time work, but I still return to Singapore often to care for my auntie. While it’s worth it, return flights add to the expenses. So I do have to borrow money from my family to make up the shortfall.

I readily admit I’ve not funded everything on my own dime and that upsets some people. They think my accomplishments mean less because I’ve had help. I get it—we all love the narrative of an inspiring, hyper-independent adventurer who’s managed to overcome all odds without relying on anyone, financially or otherwise.

I’ve seen travellers, especially younger ones, who clearly come from privileged backgrounds, but spend their time denying it so as not to be perceived as mere “trust fund babies”. But when you downplay or even lie about how much support you’ve received, it’s a slap in the face to those who have helped you. I will never be ashamed that I have a wonderful family who supports my endeavours. If anything, it’s Satan’s apology for having previously tested me with an abusive father.

3. The Art of Being Alone, Without Being Lonely

If you want to travel solo, you have to be interesting enough to enjoy your own company. I have plenty of hobbies to keep myself entertained. But you can’t always be by yourself—it can get incredibly isolating. The key is to get out there and meet people, while deliberately carving out pockets of time to be on your own. This is especially important if you’re an introvert; by setting boundaries, you retain the social capacity to properly engage with the people you meet. Sometimes they’re shy or cautious, but if you have a genuine interest in getting to know them, you’ll hear the most incredible life stories.

For example, in Qatar, I met a lady from the Philippines who was working at a high-end resort as a masseur. She was trying to save USD5,000 so she could leave her cheating, alcoholic husband. Her determination to build a better life for herself and her four children really resonated with me, because it also took me a lot of courage to get out of a bad domestic situation.

Another example was our Kurdistan guide, who shared his harrowing story of a childhood marred by conflict. He sought asylum in the UK, got thrown in jail in Iran, and eventually returned to his homeland to set up a successful tour agency.

The strength of the human condition never ceases to amaze me. It’s something you’d never learn about if you just kept to yourself all the time.

4. Islands are the Best Teachers

I’m really drawn to islands. They’re some of the best teachers we have. When it comes to issues like climate change or economic inequality, islands are often the first to show signs that something is wrong—whether it’s rising sea levels, the loss of endemic biodiversity, or the exploitation of previously isolated communities.

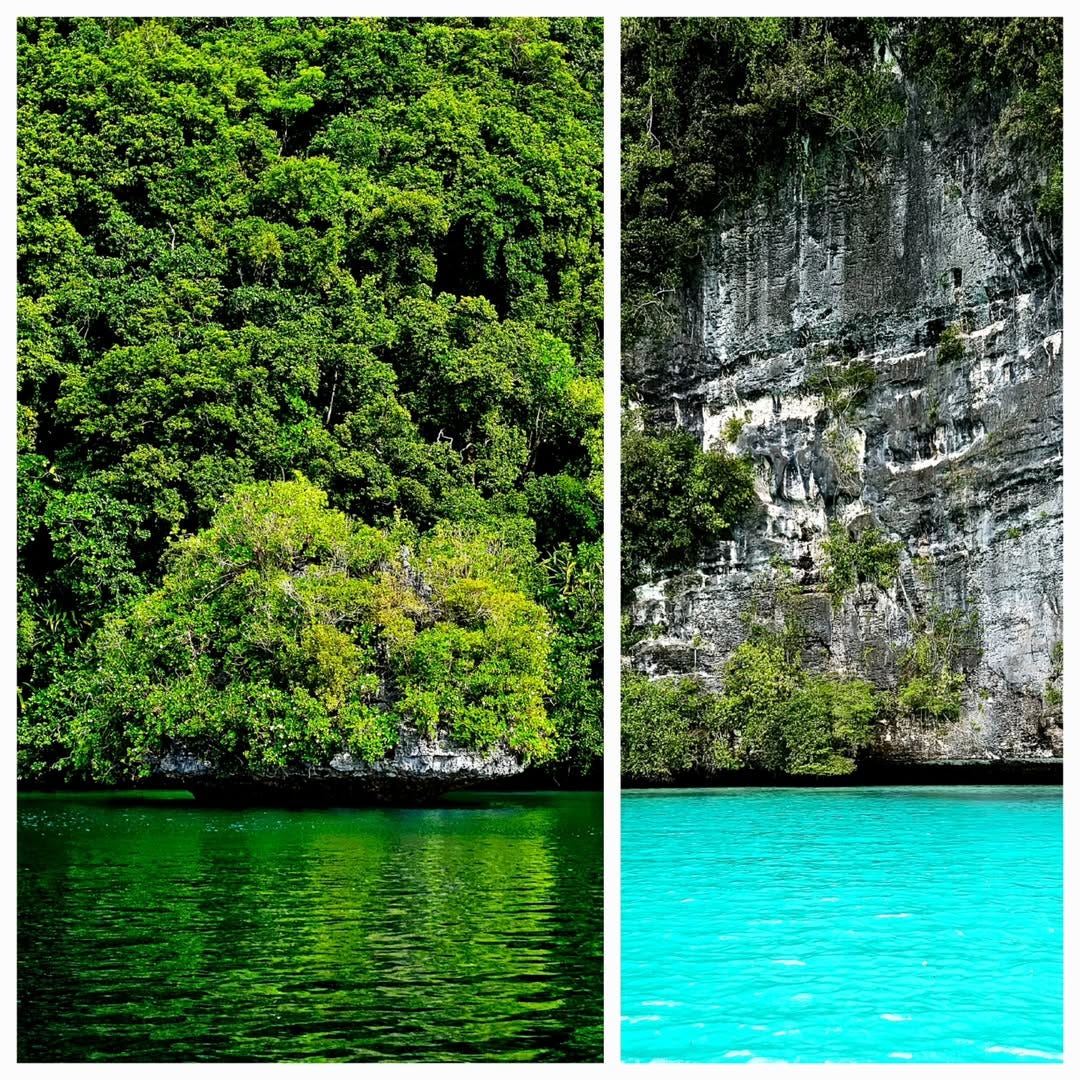

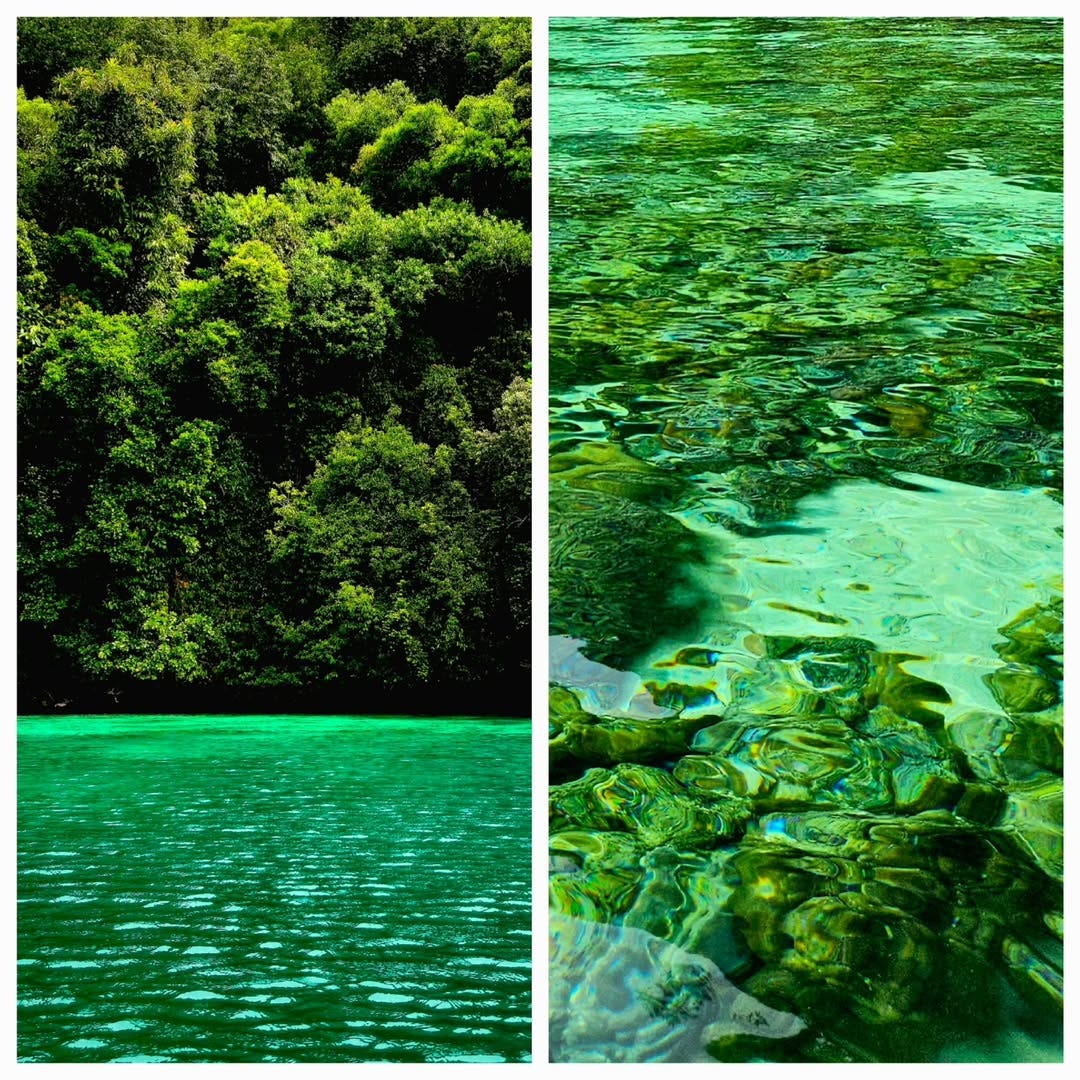

Islands like Mauritius, the Galápagos, and Palau have left a deep impact on me. The limitations of their landscapes and resources, coupled with the influx of tourism, are especially intriguing to study.

5. Dangerous Moments, and Getting Out of Them

About seven years ago, I was backpacking in Lithuania. The hostel I was staying at was fully booked, and the receptionist had allocated me a top bunk in a 24-bed mixed dormitory. I’m usually fine with mixed accommodations, and only one other person—a middle-aged gentleman from Belgium—was in the room when I checked in, so I didn’t think anything of it. At four in the morning, the other 22 occupants showed up—German tourists, all male, all drunk. They surrounded my bed, calling me racial slurs and trying to climb in with me. They tossed my stuff around and broke a table; the Belgian guy quickly got up and left.

As a woman, you don’t realise how much it’s ingrained in us to not want to appear “difficult”, even in moments when you should be focusing on your safety. Instead of telling the German tourists to fuck off, I instantly went into people-pleasing mode, laughing and smiling nervously in the hopes I wouldn’t anger them, that they would leave me alone.

Thankfully, one of them stepped away from the bunk ladder long enough for me climb down and run to the reception area for safety. An hour later, a girl checked out of the all-female dorm. I plopped myself down on the vacant bed and burst into tears. The hostel manager let me sleep there the rest of my stay. He was very apologetic, admitting that even if it was a mixed dorm, it had been pretty stupid of his receptionist to put a single female with 23 males.

Another close call was in the Galápagos in 2016. I was on a student attachment at the giant tortoise breeding centre on Isabela Island, where it was essentially my job to watch tortoise porn every day.

I got to know another female student on a biomedical internship—we’ll call her K. K was hot by every conventional measure—tall, slender, blonde hair, blue eyes. She got a lot of attention from locals and tourists alike (in comparison, I was a troll so nobody cared about me). One evening, K and I were at a bar sharing a mojito, which I was actually only pretending to drink (K had been smoking while drinking and I didn’t like that). We kept getting weird vibes from a group of Spanish tourists seated next to us, who kept hitting on K. The mojito wasn’t even half-finished when K suddenly slumped over, complaining that she was feeling unwell. I dragged her away from the Spanish tourists who were still trying to ask her out to dinner. The rest of the night was a rollercoaster—K oscillated between extreme lethargy and friskiness. Fending off multiple sexual passes from her, I took her back to her room and stood guard outside until I was sure she had gone to sleep and nobody had followed us back. It occurred to us the next morning that the mojito had most likely been spiked by the Spanish tourists (during our orientation, we had been warned about a plant growing on the islands that’s commonly used as a colourless, odourless date-rape drug).

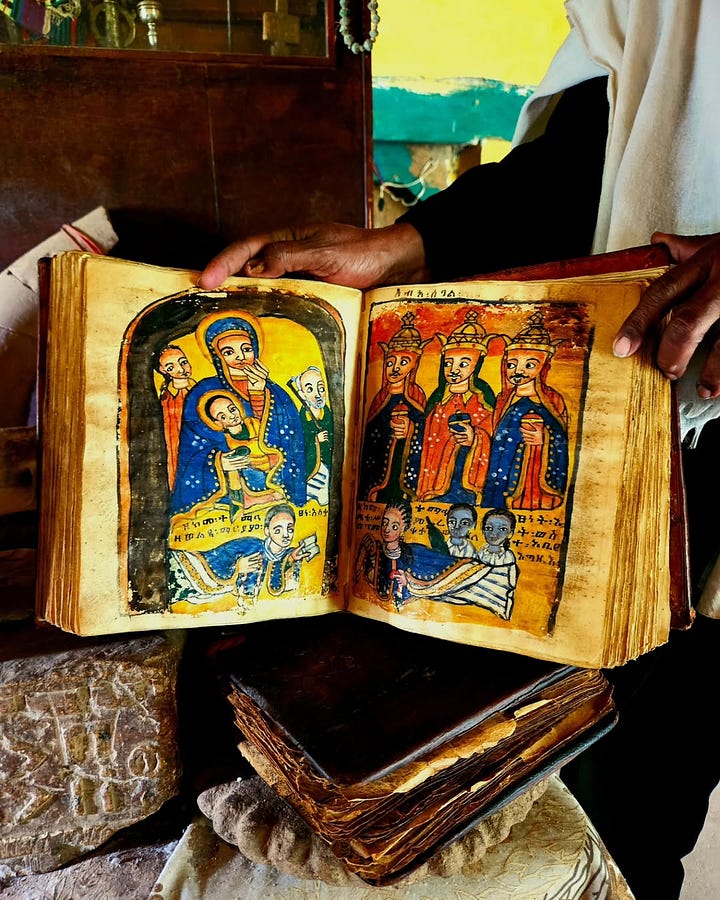

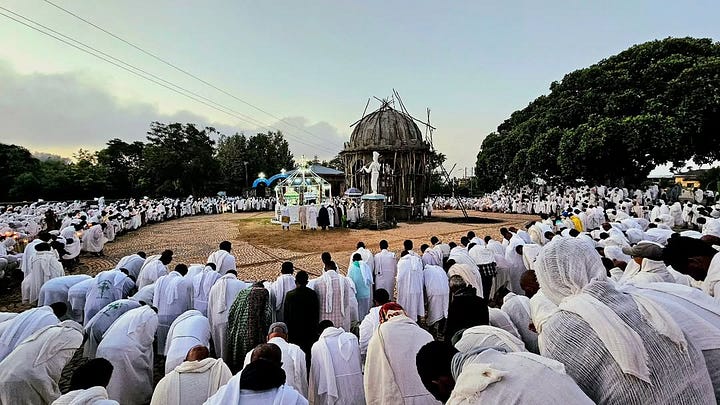

More recently in September 2024, I had a close shave while on a private tour in Ethiopia. Because of the ongoing civil unrest, the roads are not super safe; to get anywhere, it’s usually better to fly. In the two weeks I was there, I had eight or nine domestic flights. One time however, we had to travel four hours by minivan from Bahir Dar to Gondar. It was Enkutatash, or Ge’ez New Year. There were many informal checkpoints along the road manned by armed Fano guards, demanding payments of ETB50 to 250 (~USD0.40 to 2.00) before letting vehicles through. The payments got increasingly exorbitant, and by the tenth checkpoint, my driver was pissed as hell. He managed to get a signed note from one of the Fano allowing us to get through the next checkpoint for free.

Soon enough, the next checkpoint came along—a pretty busy one, with about 20 guards split between two groups. Instead of stopping to show the note, the driver simply sped past. The guards shouted at us to stop, then fired two shots at the minivan. I remember being surprisingly calm. I thought, “Huh. I guess those guns aren’t just for show after all.” The driver finally stopped, a guard leant over the window and saw I was a Ferengi (foreigner), and let us off after paying a fine of ETB200 (~USD1.50). I smelled the roses for the rest of the day.

I know I said earlier I’m not afraid of dying, but I sure can appreciate getting to live a little longer.

6. Magical Moments

I’ve travelled around many regions during their major festivals. Except for Nowruz (Persian New Year) in Kurdistan, none of this is usually planned.

In Ethiopia, I got to partake in Enkutatash festivities at a church in Gondar, and was invited to my guide’s house for a celebratory meal of doro wat (a spicy chicken stew). I also happened to be in Axum when Mihlela was taking place. Every month, four thousand people participate in candlelit processions around the church and old town to commemorate the marches of the Battle of Jericho, a practice dating back to the 6th century.

The electrifying energy of the night markets and boat races during Bon Om Touk or the Cambodian Water Festival was also something I’ll never forget. You can find magical moments even in everyday life, however small. For instance, seeing a cute dog or handsome man on the street in Bhutan always brightens my day.

7. Practical Travel Tips

When I first started travelling on my own, I would over-research everything. This isn’t fair to new destinations, because you often arrive with a judgmental outlook and preconceived notions.

Nowadays, I do the bare minimum. I have a basic itinerary and rely on local guides to tell me what I don’t know. I usually find them online or through recommendations from friends. Granted, they can be a hit-or-miss; I’ve had guides who didn’t know their material, tried to fleece me, or even proposed marriage to me. You learn to accept it as part of the unpredictability of travel.

Your experience of a country tends to improve when the elements are on your side. To save money and still catch pleasant weather, I often travel during shoulder season. It also helps not to be too caught up in planning and organisation. I learnt this the hard way when I applied for my Kuwait visa too early and found out it had expired after I entered the country.

Finally, rest is so important! I experienced severe travel fatigue in South America and skipped most of the sights in Rio de Janeiro, including Christ the Redeemer and Copacabana Beach. Returning to Singapore, I slept 18 hours a day for a week to recover. If you want to travel long-term and remain healthy, you need to be fine with not hitting every attraction in favour of an early night in.

8. Key Travel Skills

Be flexible and open-minded. You might not agree with certain rules or cultural practices, but as a guest in a foreign land you have to be mindful of them.

In many parts of Northern Africa and the Middle East, I initially felt uncomfortable that I had to cover my head when visiting holy sites or participating in religious events. I just couldn’t fathom how my exposed hair was seen as immodest. But that’s the way of life in many of these countries, and it adds nothing of value to be an entitled asshole expecting others to accommodate you. At the end of the day, it’s about making an effort to understand local customs, even if they challenge your own beliefs. Respect is non-negotiable.

9.Surviving Physically Challenging/Extreme Environments

In 2023, I trekked across the Namib Desert as part of an all-female team for charity. We covered 144km over five days, raising USD70,000 for women survivors of war. This meant a lot to me, as it was a comeback after sustaining a workplace injury in 2022. I had thrown myself into training after receiving medical clearance just three months before the trip. Still, the treacherous terrain of the Namib almost took me out: on the third day of the trek, I sprained my knee descending a mega-dune and had to be administered painkillers in the middle of the desert. Limping the rest of the way, I was the last person to cross the finish line.

It takes a lot of fortitude to overcome such an extreme environment: sinking sands, scorching heat in the day, sub-zero temperatures at night, gale-force winds. In situations like these, support from your teammates is critical.

The Iron Ore Train in Mauritania was another extreme experience. It’s one of the longest, heaviest, and most dangerous trains in the world, and it’s technically illegal for people to ride in open-top carriages. I snuck onboard the night of Dec 31, 2024 with a group of like-minded tourists/adventurers/idiots. We rode the train into the new year, getting sporadic snatches of sleep on the powdery black ore, and watched the first sunrise of 2025 appear over the Sahara.

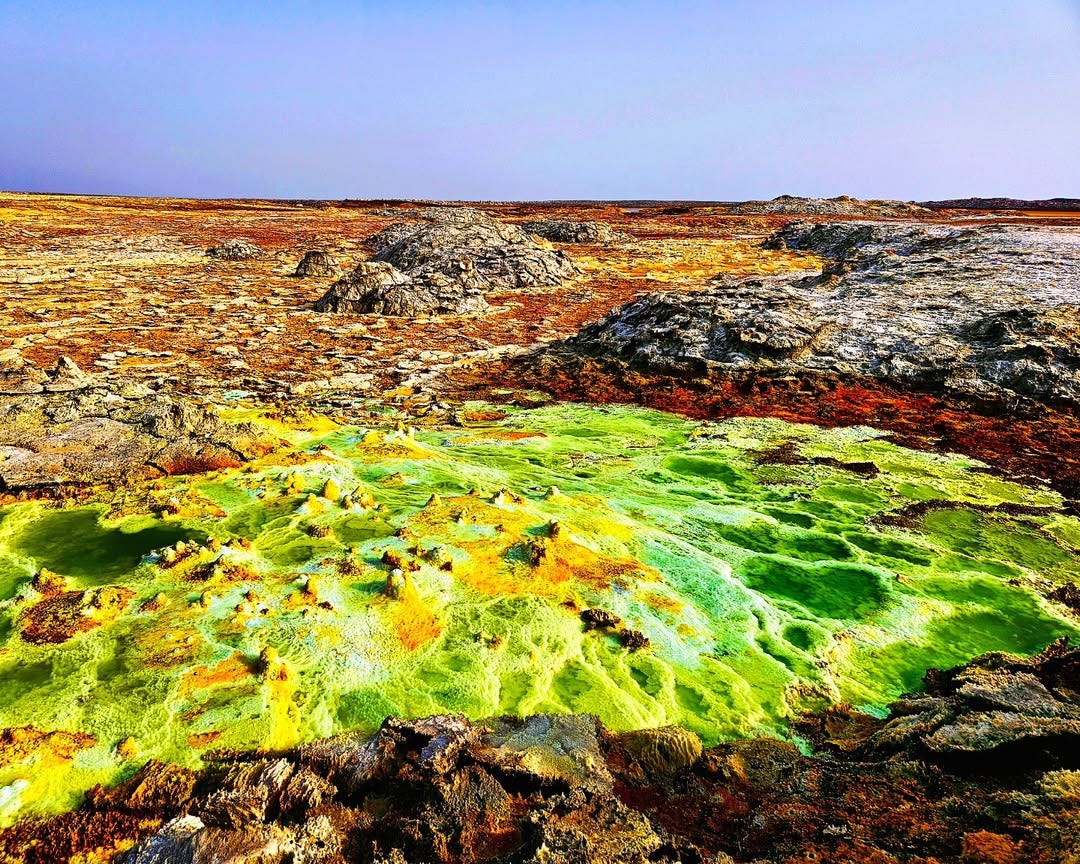

The Danakil Depression in Ethiopia was one of the most surreal places I’ve ever been to. With daily temperatures reaching up to 50°C, it’s one of the hottest, driest places on Earth. The heat was oppressive even at night, and we were guzzling at least three times as much water as usual.

The landscape of the Danakil is like nothing I’ve ever seen—great salt lakes, neon hydrothermal pools, active volcanoes, soils so parched they crack like roof tiles. It was straight out of a sci-fi movie.

10. The Need For Responsible Tourism

I’ve definitely witnessed the effects of environmental degradation and over tourism in many of the places I’ve visited. You can’t be a hypocrite about it: anyone who’s ever travelled has likely contributed to the problem. I think it’s funny that many of us say “over tourism is bad” in the same breath as “OMG we FOMO we should visit this place ASAP”. Everybody wants to stop over tourism, but nobody wants to stop being a tourist, myself included.

We give a lot of flak to the authorities and locals of touristic destinations for not doing enough to protect the environment and resident communities. But people do whatever is necessary to put food on the table for their families, even if that means letting tourists touch or ride endangered animals.

So as tourists, what can we do? Simply don’t be an asshole.

Don’t vandalise forests, pressure guides for access to restricted areas, and shove cameras into people’s homes without permission. If tourists act like they actually give a shit about the places they travel to and the people who live there, hopefully the locals will pick up on that, and feel assured that they don’t have to compromise their home to earn a living and make their guests happy. People are more likely to change when they are inspired, incentivised, or empowered to, not because a foreigner has come along and ordered them around.

Also, call out businesses from wealthy nations who criticise so-called “third-world countries” for “not being environmentally friendly”, but are actually in huge ecological debt to them. Countries and organisations that appear “sustainable” are often only so because they outsource their non-green activities to poorer countries, using them as dumping grounds and buying their resources at exploitative rates. It’s easy to villainise such countries for being “uncivilised” when our hands aren’t tied behind our backs.

What’s Next?

After all her travels, there’s still nothing like home. Yi Rong tells me she loves Singapore, small as it is. “We take a lot of things for granted,” she says, acknowledging how easy it is to talk shit about the country.

“But we’re really lucky to live here. It’s safe, compact, and a jumping point to anywhere in the world. There’s a freedom in that, but somehow, we’re always stressed out. There’s this strange duality of living in a place where everything is at our fingertips, but we don’t always feel free or happy.”

And of course, Yi Rong has a slew of travels lined up for the foreseeable future. At some point, she hopes to return to Ethiopia to visit the Omotic tribes in the south. And North Korea or Afghanistan? Never say never. Yi Rong isn’t one to shy away from an adventure, no matter where it takes her.

On how travel has changed her, Yi Rong says, “It has emboldened me. The world is a pretty cool place once you get to know it. About all the shenanigans I’ve partaken in thus far, there will undoubtedly be more to come, and I’m sure I’ll be able to get out of them alive.”

“People call me unhinged,” she quips with a grin. “But really, my love for the world, like my impropriety, knows no limits. And that’s how I want to live.”